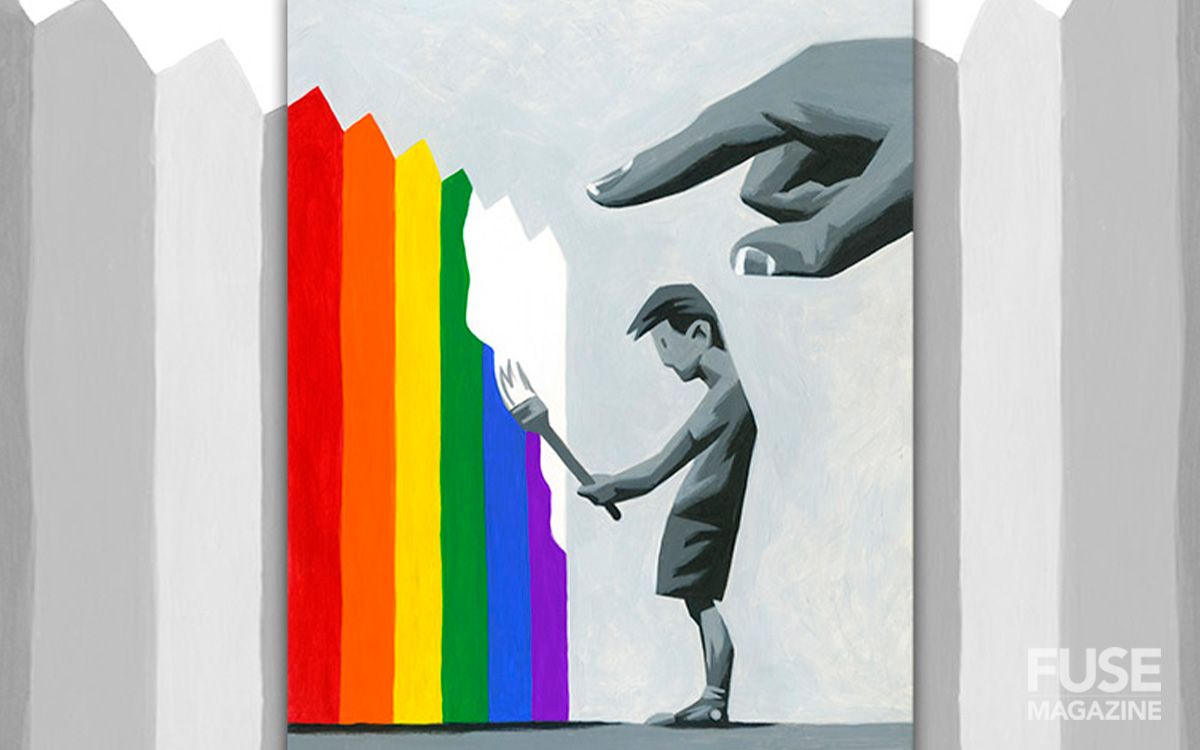

Kazakhstan bans LGBTQ+ 'propaganda' amid local support and activist concerns

Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has signed a new law banning what authorities describe as LGBTQ+ “propaganda, a move that has drawn both local support and sharp criticism from human rights advocates and LGBTQ+ communities.

Activists warn it could be used to suppress advocacy and public support under the guise of “protection.

THIS ARTCILE IN SHORT

- Kazakhstan follows Russia in banning 'LGBTIQ+ propaganda”.

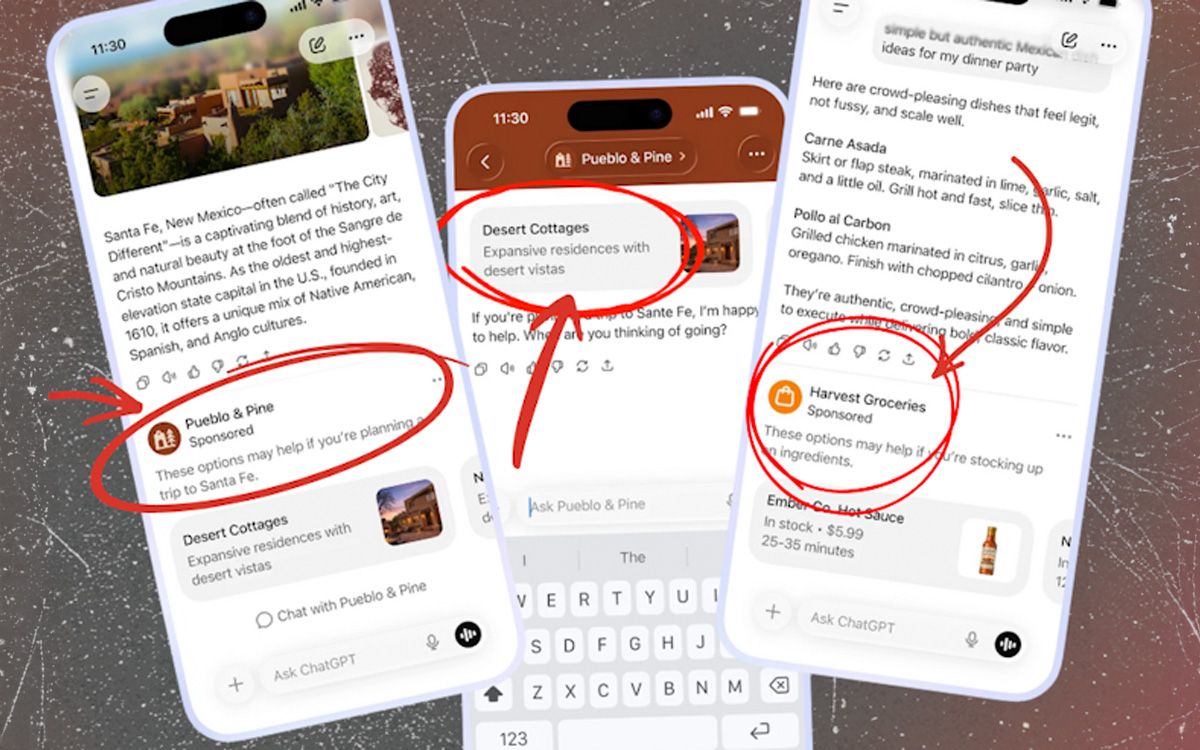

- The law will apply across all media, online platforms and public spaces.

- The law uses vague and undefined language, raising concerns about how it will be enforced.

- Queer activists warn it could be used to silence visibility, advocacy and free expression.

- The government insists that being LGBTIQ+ is not illegal, but limits public support or promotion.

The law, signed on 30 December 2025, restricts the dissemination of what it labels as “propaganda of paedophilia and non-traditional sexual orientation” across social and public media, online platforms, and public spaces. It also targets what it calls “deliberately distorted information” intended to create a positive public perception among an undefined audience.

The legislation introduces amendments to **eight existing laws**, including those covering children’s rights, education, mass media, advertising, culture, cinematography, online platforms, and the protection of children from harmful content. Notably, these changes were introduced through amendments to laws governing archival materials, a process that has also raised procedural concerns.

President Tokayev has previously criticised what he calls the global “LGBTQ+ agenda”, framing it as foreign interference. Speaking at the National Kurultai in March 2025, he claimed that LGBTQ+ rights had been imposed on countries under the guise of democratic values, alleging misuse of international funding by non-government organisations.

Concerns Over Vagueness and Enforcement

Critics argue that the law’s wording is **unclear and overly broad**, offering no precise definition of what constitutes “propaganda” or how violations will be identified. LGBTQ+ activists fear this ambiguity will allow authorities wide discretion in enforcement, potentially leading to censorship, self-policing, and the suppression of queer visibility.

Government officials have sought to reassure the public that the law does not criminalise LGBTQ+ identities themselves. Yelnur Beisenbayev, a member of the Mazhilis (the lower house of parliament) and one of the law’s initiators, stated that personal behaviour is not prohibited.

“If, for example, two men hold hands in a park, that’s not considered propaganda,” Beisenbayev said. “It’s their personal boundaries.”

However, he added that people are not permitted to publicly invite others to participate in or express support for LGBTQ+ movements — a distinction that activists say effectively bans advocacy and public affirmation.

Human rights groups warn that the law could have a chilling effect on freedom of expression, access to information, and the safety of LGBTQ+ people in Kazakhstan.